On 20th March I gave my inaugural lecture as Professor of Management and Organisational Learning at the University of Chichester. Here is a written up version of that lecture.

A few years ago in a charity shop I picked up this book by the physicist and polymath Richard Feynman. Here is someone who was curious about the world and did not let professional or academic boundaries constrain or define him, despite being a Nobel Laureate and professor of theoretical physics at Caltech.

In a visit to the islands in the South Seas he noticed that the islanders had created grass strips with fires lit down each side to look like runways, with huts to imitate air traffic control and headgear to mimic comms equipment. This was a decade or so after the end of WWII, which for them was a time of plenty, with goods and materials brought to them by cargo flights to support the war effort in the Pacific, but now long since gone. In his chapter about Cargo Cult Science Feynman was making a wider point. As with the islanders’ efforts to entice the gods from the sky to bring them the goods they now missed, how do we know we are not deceiving ourselves by just looking at outward appearance rather than developing deeper understanding and curiosity. He pointed out:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest (Feynman, 1999).

He was talking about science, but clearly this observation has wider implications. The implication being that if we replicate what we think we want, but without the deep understanding of what it is, we will be frustrated that we do not see the outcomes we hoped for. Also notice he is pointing to a duty to oneself, but also to others – there is a social and community dimension.

The question I come to is: how do we know that we are doing any good in education and development? In my field of management and leadership education, how do we do any good? I do not think it is an answer that can be assumed. This is despite all of the educational infrastructure and procedures that define what courses we offer and how they are taught. For me at least, it is a question that is always on my mind – it is a matter of ethics. The questions extends to organisations too – how do companies, hospitals and government administration create a culture and nurturing environment to enable learning to occur to serve that organization well in an increasingly unstable and fluid world?

In a very practical way, by sharing stories of my own experience in leadership and management, as a practitioner, researcher and teacher, I will try and address this question as it applies to the field of people and organizational development. I may well make some provocative remarks to the effect that what is of value and makes a difference may well not be what we readily talk about, notice and measure.

I have always been interested in understanding working life, not from the sidelines, but as a player on the pitch. This makes me unusual as a management and leadership academic, where there is a tendency to see organizational life as a petri dish examined from a safe distance under a microscope. Perhaps my interest and approach stemmed from my late teens and early twenties working as a cashier in a betting shop for a year, managing a snooker club, or from my brief stint as a nightclub bouncer. In short, all life was there: warmth, humanity, danger, tragedy, cruelty, and humor. Above all, I quickly came to realise that people are fascinating; their histories, the choices they make, the stories they tell and how they relate to the people around them. And then of course, how I related to them.

But life has odd twists and turns, and my first ‘proper’ gig was as a medical microbiologist after completing a degree in microbiology and virology, which as you can already tell, still frames the way I see the world and the metaphors I draw on. So what has happened between then and the moment we are gathered here today – and how might reflecting on that shine a light on management and leadership development going forward?

I have made a few other stops along the way, ranging from working as a consultant for an environmental start-up company looking at sick building syndrome and legionnaire’s disease, civil and structural engineering, to the National Blood Service. I became increasingly interested what I was doing in that petri dish along with everyone else I encountered. I was intrigued by where we worked, our environments, and how this affected the way we saw the world – laboratories, offices, transport, the outdoors, places like this; they change us. Merchant banks, the military, the Civil Service, publishing, manufacturing all had their particular mores and ways of doing things, which oddly they were largely blind to.

But it was when working for the National Blood Service, latterly NHSBT, that I started to put the pieces together. And those stories of warmth, humanity, tragedy, cruelty, and humour continued with even more richness and fascination. This was particularly the case when I compared such experiences to the accounts for how organizations should be, written by professors, business gurus, and retired business titans after gazing down their smartarse-post hoc microscopes.

I will give you a personal example:

I was in my early thirties and had been with the National Blood Service about two years and had been working on a collaborative project with a very prestigious university on a microbiological containment laboratory. I had a routine meeting with the Principal Investigator, she was a Chinese American woman married to a French scientist who had served a prison sentence in France for his role in the contaminated blood scandal there. The office was meticulously clean and laid out, including a highly polished desk with a small oblong planter with grasses in it that caught my eye for some reason. We sat around an empty polished table in front of her desk. We were working through a document about how this laboratory would function, it would be working on atypical HIV cases from Africa, when we got onto to topic of who would carry the can if it all went wrong. At that moment everything changed and she became angry and animated, stood up and leant against her desk looking down at me (which I now reflect was a well-played out routine). After about 10 minutes she picked up the phone to the CEO, a very sharp-witted professor from Chile. All of a sudden, I felt the whole world was in that room looking at me. People say there are two stress reactions – fight or flight, I found a third, staying put and seeing what happened. Despite feeling angry, frightened, emotional and aware of physiological changes to my body in terms of blood pressure and a reddening face, I felt oddly detached at the same time, I was an observer of my own experience. In that moment of detachment I realized that in staying put looking clearly into the eyes of the person staring down at me, I had agency, I was not powerless.

Eventually it ended well and to my liking. To this day I find experiences like this fascinating by shining a light on power, agency and culture. Clearly this story is unique to me, but everyone has stories like this, stories that can be easy to dismiss or trivialize, but yet offer so many reflective learning opportunities. To my mind they offer a far richer source of learning than case studies that we commonly find in management and leadership studies. With our experience, we are on the pitch in a game that matters to us, we are not on the sidelines watching a game where the whistle has long since been blown and where we have no stake. Some years later after gaining my MBA and having been promoted a few times, I found myself on the corporate business planning group representing Human Resources. My interest in power, agency and culture had developed considerably, both theoretically and on a practical level as my next example demonstrates.

The bulk of Business Planning was done in Wakefield, Yorkshire during a two-day event ahead of the Executive Team meeting, the Board and the Department of Health so they could have their input and signoff. But it was not anywhere in Wakefield, we had fallen into the habit of meeting in this castle-come-wedding venue. It was located on an island in a large lake with a small drawbridge. We met in a big room with chintzy curtains and wallpaper that was neither pink nor orange, but some strange place in between, along with round tables, PowerPoint projectors and flipcharts. Since arriving the night before, and oddly having been allocated the bridal suite, this setting was starting to bother me. What happened next was a verbal culmination of these concerns that in the spirit of improvisation surprised me as much as the others in the room. During a pause when we were talking about workplace culture, I playfully introduced the notion of metaphor and symbolism and offered a practical example – what does a castle, moat and drawbridge say of an organization’s culture, and how might it affect the conversations and perceptions? I then drew attention to how some facilitators were standing up and pacing up and down, meanwhile us contributors were sat down over our flipcharts, extending the metaphor from a castle to a prison.

The meeting could have gone several different ways, but I knew most people well and had a good relationship with them. In that moment it seemed a risk worth taking. It created an opportunity to talk about the culture that we were hoping to develop and the methods that we were using in our business planning. A few months later I was asked to join the strategy planning team to develop this further.

This move coincided with the start of doctoral studies into organizational change. It was a research community that used complexity sciences as an analogy to explore organizational life (Stacey et al., 2000). At this point I would like to thank my supervisors, Professors Ralph Stacey and Patricia Shaw, and others, for the enabling me to see the world differently and to further develop my interest with the everyday organizational life around us. I was researching how government and organizational healthcare policy comes to change what people actually did on the ground, for example with patients, or in my case with regard to organ donation. On the face of it, policy and strategy is made, budgets are agreed, change programmes are created, implementation occurs and we get the benefits that we hoped for. But I knew, as Head of Strategic Change by then, that life was not as simple. It is a topic that still intrigues me to this day and has morphed into the topic we are exploring here.

I am going to pause there to recap, before introducing a little theory. First, everyone has a story that is interesting and relevant to them when it comes to their own learning and development. My Wakefield story verged on the naïve, clumsy and haphazard. My actions and decisions created further reactions, ripples and conversations that then unfolded in ways that were both congruent with the norms and customs of the group, but there was novelty too. Something new was created in those moments of improvisation. Perhaps my naïveté was obvious to some members of the group, who were amused and forgave my clumsiness. Or perhaps to others it did not seem clumsy at all, but rather playful, as is my tendency sometimes. Or, both. Mistakes, missteps and successes are subjective and inter-relational, they do not only exist as quantified metrics to be notched on a scorecard. They can be created, damaged, misrecognized and destroyed in a moment in the hurly-burly of our interaction.

Given the richness of our own experience, why would we want to delegate our learning to abstract Case Studies of situations where the outcome is known, and where we have no stake in the game? I say this because I see an over-reliance on the Case Study (Yin, 2011) as a means of management and leadership learning, and I think this is wrong.

Now is perhaps the right time to dip into a bit of theory, namely an idea from Hannah Arendt. To many, Arendt was a political theorist or moral philosopher, in fact the jury is still out as to where her contribution lies, but to me she is particularly helpful in exploring organizational and wider societal processes as to how we get on with each other and make the choices that we do – for good or ill. It is dangerous to attempt to distil Arendt’s ideas: to do so loses the meticulous argument she builds. In her book, the Human Condition, she explores the nature of how we live an active and contemplative life, and in doing so draws our attention to three important qualities, these were labour, work and action. In essence, labour is what we need to keep us alive: food, fuel and shelter. Work is what we create and build, the artifacts around us in physical and non-physical form that stand the test of time. However, action is ephemeral, it is what we do together but then evaporates as soon as we walk away, it has no legacy other than in the minds. It is how we reveal who we are to others and how they reveal who they are to oursleves – and in doing so we develop, learn and move on. It gives us life and a sense of who we are (Arendt, 2018) I am now going to focus on the interaction between work and action: what gets recognized and what is easily forgotten. To start this off I am going to do a bit of personal time travel that surprised me.

I completed my doctorate fourteen years ago. Key to the doctoral process are the conversations with one’s doctoral supervisors. Here the aim is to support and encourage the doctoral student and to give advice on the next step to take in their research. I would always record these conversations to make sure I did not miss any precious nuggets. In preparing for this talk I listened to one of my last conversations in 2010. Listening to those words was like going back in a time capsule, I could visualize my supervisor’s apartment and the view over the Thames in West London and the smell of coffee. I remember my lack of confidence and struggling to find the words to articulate myself and how Patricia somehow caught my thoughts before they reached my tongue. In listening to those words and other sounds, that whole experience came back to me and at the same time brought me bang up to date as an experienced PhD supervisor with my own students. And in a way it made me shameful of my own practice today, often I would see a supervision session as one more meeting in a very busy day. I would forget the experience of being supervised: of risk, jeopardy and trying to make my point when the way forward seemed so foggy. Listening to the recording was humbling, yet it would mean very little to you if you were to sit with me to listen to it.

Personal development, for example in leadership, it is inherently personal, context-specific and identity forming; it is largely subjective and intersubjective. By now, you may be sick and tired of me talking about me. In fact, self in a social context goes to the heart of what I think is important about research and the teaching of leadership, and is often notably lacking. It is the story of the social self (Burkitt, 1991), undertaken in a reflexive and critical way, that is key to personal development and wider knowledge. Done well, it can take important philosophical ideas and bring them face to face with our reality; in other words we have the opportunity to make a practical bridge between ideas of our time and our leadership practice that matters to us and to those around us. As an academic discipline, it is a process of auto-ethno-graphy – a story of self, of people and culture, and the study of (Ellis, 2004, 2007; Ellis and Bochner, 2006; Sparkes, 2017). In the examples that I have given here, there are signs of logic, emotion, risk, live interaction, reflection, fear and so on, or of practical knowhow: evidence of phronesis as Aristotle might have called it. Clearly these are events that mattered to me – I was on the pitch, but I hope they might have some resonance with you. Coming back to Arendt, I am paying attention to meaningful action as opposed to artefacts of that we can find so readily at hand which so easily catch our attention in organizational life. Arendt says of action that:

Since we always act in a web of relationships, the consequences of each deed are boundless, every action touches off not only a reaction but a chain reaction, every process is a cause for unpredictable new processes. This boundlessness is inescapable; it could not be cured by restricting one’s acting to a limited graspable framework … (in Bernauer, 2012)

The ripples that we cause, and that are subjected to the action of others, should be a source of curiosity in our own development. More importantly, those ripples should be a source of inspiration for how we develop people and organisations. I will now pay attention to this process.

Just a quick overview in relation to people and organization development. For the sake of convenience, here, I am going to make a bit of an artificial distinction between people and organizations. First, we have the MBA and Senior Leaders’ Apprenticeship programme. These are open to anyone with suitable experience to apply – here we focus on the development of the person in a practice-based learning context. Second, there is a Post Graduate Certificate in Leadership and Management which is a third of a masters degree. Here we offer programmes to an organization as part of a more coordinated agenda for development to address a corporate problem or opportunity, for example it might be a troublesome merger. Here again, participants develop their learning in practice-based situations.

So what might the experience of being on a programme feel like, and what are the philosophical foundations? And how is this structured in a practical way?

You might have noticed the picture of the South Downs by Eric Ravilious on the first picture. All too often we see what is around us as fixed or reified, we convert experience into objects. We talk about the organisation or the University as a thing, whereas we could talk about the action of organising. This was an idea explored by Gilbert Ryle in the 1950s in Concept of Mind – he called this (mis)conception a Category Mistake (Ryle, 1949). It is easy to see our landscape as fixed, and we want to keep it that way, but all sorts of pressures and powers are at play to constantly change it – us humans, geology, other animals, plants and fungi – all exerting their influence. But we need to work hard to notice these forces; the same is true for our organisational life.

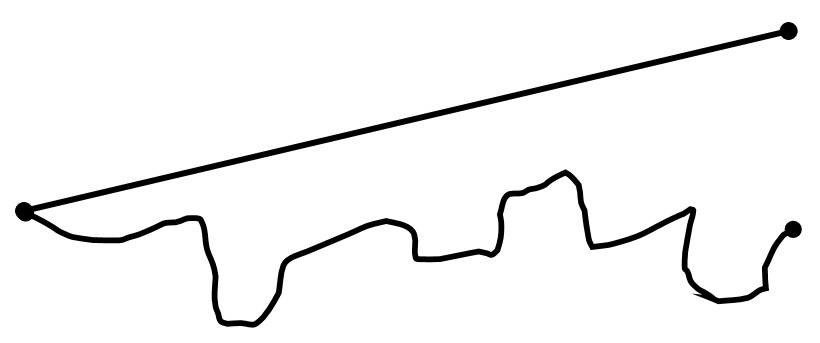

What does all this mean practically? I am going to start with a diagram that I hope illustrates this.

In summary, the top straight line represents the hopes we have for the future our plans, policies and strategies might bring to life. The wiggly line below is what actually happens, along with the ups and downs on the way, and even then we may not get to where we hoped. Both sets of lines are represented in participants’ leadership and change management assignments[1]. I am not saying one is any more important than the other – in fact, both are needed; the problem is that we typically notice and stress the straight line over the twists and turns of our experience.

The straight line is easily seen in our world of work. We have strategies – some detailed and complex, some small on one page. They may have photos of delighted customers, students or service users, or some image designed to inspire. There maybe charts and graphs that imply the future is assured, all we have to do is allow the future to seamlessly unfold. In my doctorate in healthcare policy I was fascinated by these documents and the conversations and meaning-making they created. We have frameworks and models that help us understand and act in the world, often presented as a 2×2 matrix. And then to crystallize our efforts and to reassure us, we have targets that articulate in numbers what this future will look like. And when we get to that future, we will know the implications for missing or exceeding those targets. There is an epistemic assumption that the world is there to be known in its abstract and generalized form, we just need to work it out. Going back to Arendt’s ideas, I see these artefacts and outputs as ‘work’, they are important as they create propositions around which we take action, we allocate resources and are held in our action.

Early on in the masters programmes, participants are required to talk with their colleagues to come up with a personal change or leadership project. It has to be a project that matters to the participant and the organization, designed to create ripples of learning and noticing – in other words it needs to affect the process of organizing and how people relate to each other in some small way. The ‘artefact’ might be a strategy, a consultancy proposal or project brief. It will outline for example the aims, how the project will be carried out and the resources needed.

Now for the wiggly line. Events never pan out quite as planned; the learning is in how we act and the ethics we bring to our decision making. It is in those day-to-day practical experiences that we and others are sometimes found wanting, and have to work things out together. I have outlined a few of my everyday experiences; you might want to think of some of your own recent work experiences: what have been the striking moments (Shotter, 2005)that have surprised you; think about something pretty ordinary and look at it carefully – was it that ordinary, was it ordinary for the other people you were with? What did you do, how did they respond, where are you all now? Did you talk about that strategy or policy? If so, what did you talk about? How did you understand it and what decisions did you take? The deeper you look, the more interesting it is.

And if you are a participant on a leadership programme, how is your agenda, as articulated in your strategy or proposal, coming along? How is it being buffeted by the interactions and sensemaking of others? This is the close at hand learning that is present in our everyday work. This is the action that Arendt was keen to stress, the importance of which is by its nature so ephemeral. Arendt was heavily influenced by Socrates and Aristotle (Simmons, 2012), particularly stressing social dimension of knowledge. Aristotle called it phronesis, or practical wisdom, of how we learn from real world by our interaction with others. You would write accounts of what had occurred, what had surprised you, and how you reacted with those around you to negotiate the next step.

The question is this: as faculty what role do my colleagues and I have on the programme? Clearly, we need to stand up and lecture on the various ideas and concepts to do with strategy, leadership and the like – all important stuff. But I believe our value comes in the conversations we have with participants to enable them to see their world in a new light so that they can work their way through problems and opportunities. It is more of a coaching relationship. It is also important to create a nurturing environment where participants share their own experience, curiosity and learning, and it is here that I believe that learning really starts to matter. And it is where I learn too. In short, it is to be part of that social flux where we take action together, rather than me being distant or disconnected from the participants’ experience.

So what work is produced? I am keen that participants produce outcomes that are meaningful for them both in the words that they use and in the form it is produced. We are more than words on a page, and assignments should reflect this. We communicate and understand our world in the language as well as in what we see and what we hear. Assignments are reflexive, they chart the nature of experience and invite further critical exploration of the everyday and their action. Thoughts and ideas of philosophers and management scholars are used to shine a light on that experience, but the offer is left open to artists, poets, music, novels and other ways by which we come to understand the world and our place and agency in it.

To return to Feynman’s invitation through the metaphor of the Cargo Cults, I repeat the question: What good do we do? And the risk that in replicating what we think we want, but without that deep understanding, we miss out on the outcomes we need. A recent study from the Chartered Management Institute (Are graduates ready for work? New CMI research – CMI, n.d.) determined that 80% of employers believe graduates aren’t work-ready on entering the employment market. And what are those qualities that are in such short supply? They include: team-working, problem-solving, communication, self-management, flexibility and adaptability, initiative and self-direction, emotional intelligence and creativity. It’s the stuff of the wiggly line, it’s the action in Arendt’s language, it’s the everyday interactions that we have. I sometimes worry that getting students to write strategies, prepare project plans, to write an essay on a case study is falling into that Cargo Cult Trap, particularly if they are disconnected to the ongoing, messy shenanigans or organizational life. It is why placements and work experience are so important. Management and leadership is not a spectator sport, it is a performance – a high stakes game to be played.

Clearly, I am talking about the development of people, but from my experience the same is the case in organization development or the activity of organizing. The core problem (and our way forward) is how people get on with people, and how these ripples travel across the processes of organizing that we are part of.

As we look forward to a world that is increasingly shaped by Artificial Intelligence what do we have left, what might become even more important? Perhaps one place to look is the action that we undertake together to understand our world and make sensible choices.

To finish, I think we need to have a better way to talk about our organizational life that gives recognition to our everyday action that we do together. But here lies the rub – as soon as we find words, we also tend to cement them into our consciousness and language, they become fixed. Despite this contradiction, I hope I have outlined not only the problem, but some practical ways forward to improve management and leadership development.

References

Are graduates ready for work? New CMI research – CMI (n.d.). Available at: https://www.managers.org.uk/knowledge-and-insights/news/are-graduates-ready-for-work-new-cmi-research/ (accessed 5 January 2024).

Arendt H (2018) The Human Condition. 2nd ed. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Bernauer JW (2012) Amor Mundi: Explorations in the Faith and Thought of Hannah Arendt. Springer Science & Business Media.

Burkitt I (1991) Social Selves – Theories of the Social Formation of Personality. London: Sage.

Chia R and Holt R (2023) Strategy, Intentionality and Success: Four Logics for Explaining Strategic Action. Organization Theory 4(3). DOI: 10.1177/26317877231186436.

Ellis C (2004) The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel About Autoethnography. Rowman Altamira.

Ellis C (2007) Telling secrets, revealing lives: relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qualitative Inquiry 13(1): 3–29. DOI: 10.1177/1077800406294947.

Ellis C and Bochner A (2006) Analyzing Analytic Autoethnography : An Autopsy. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35(4): 1–21.

Feynman R (1999) Cargo Cult Science: Some Remarks on Science, Pseudoscience, and Learning How to Not Fool Yourself. In: Robbins J (ed.) The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman – The Pleasure of Finding Things Out. Penguin Books, pp. 205–216.

Ryle G (1949) The Concept of Mind. London: Penguin.

Shotter J (2005) Goethe and the Refiguring of Intellectual Inquiry : From ‘ Aboutness ’ -Thinking to ‘ Withness ’ -Thinking in Everyday Life. Janus Head 8(1): 132–158.

Simmons W (2012) Making the Teaching of Social Justice Matter. In: Flyvbjerg B, Landman T, and Schram S (eds) Real Social Science – Applied Phronesis. Cambridge University Press, pp. 246–263.

Sparkes A (2017) Autoethnography comes of age: Consequences, comforts, and concerns. In: Beach D, Bagley C, and Silva M da (eds) Handbook of Ethnography of Education. London: Wiley.

Stacey R, Griffin D and Shaw P (2000) Complexity and Management – Fad or Radical Challenge to Systems Thinking? Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Yin L (2011) Applications of Case Study Research. London: Sage.

[1] The interaction between the wiggly world of happenstance and our propensity towards the linear world of planning and assurance is nicely explored in a recent paper by Robert Chia and Robin Holt (Chia and Holt, 2023).